Shefa-'Amr

| Shefa-'Amr | |

|---|---|

| Hebrew transcription(s) | |

| • Hebrew | שְׁפַרְעָם |

| • ISO 259 | Šparˁam |

| • Also spelled | Shfar'am (official) |

| Arabic transcription(s) | |

| • Arabic | شفاعمرو |

|

Shefa-'Amr

|

|

| Coordinates: | |

| District | North |

| Government | |

| • Type | City |

| • Mayor | Nahed Khazem |

| Area | |

| • Total | 19,766 dunams (19.8 km2 / 7.6 sq mi) |

| Population (2009) | |

| • Total | 35,300 |

Shefa-'Amr, also Shfar'am (Arabic: شفاعمرو, Šafā ʻAmr; Hebrew: שְׁפַרְעָם, Šəfarʻam) is a predominantly Arab city in the North District of Israel. According to the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), at the end of 2009 the city had a population of 35,300.[1]

Contents |

Etymology

In the Roman Era, the town was known as "Shofar Am", Hebrew for "horn of a nation". It is thought that this name is derived from that of the Jewish Sanhedrin, which for a time was located in the city and was considered the nation's horn. Alternatively, the name could be based on the literary Hebrew word shefer שפר, meaning "beauty" or "goodness", i.e. "the beauty of the people". According to a popular Arab legend, the Arab general Amr Ibn Al-Aas was cured of an illness after drinking the local water. Upon seeing their commander's recovery, his soldiers cheered "Shofiya Amr" (Arabic for "Amr was healed"), and that was the source of the name. The spring from which he allegedly drank is located southeast of the city. Others allege that the name "Shfar-am" was changed to an Arabic form "Shefa-'Amr" in the Mamluk period.

History

Archaeological research in Shefa-'Amr indicates that the area has been inhabited for centuries. It is unclear who the early inhabitants were, although they may have been Canaanites. Shefa-'Amr is mentioned in the Talmud as one of the cities that contained the seat of the Jewish Sanhedrin. It is again mentioned in connection with Jewish revolts against the Romans, and Jewish graves and remains in caves dating to the Roman era of rule in Palestine have been found there.

Shefa-'Amr contains Byzantine remains, including remains of a church and tombs.[2] Under the Crusaders the place was known as Safran, Sapharanum, Castrum Zafetanum, Saphar castrum or Cafram.[3] The village (called "Shafar Am) was used, between 586-590 H., by Saladin as a military base for attacs on Acre.[4] By 1229, the place was back in Crusader hands, and it was confirmed as such by Sultan Baybars in the peace treaty of 1271 C.E. (670 H.), and by Qulawun in 1283. However, it apparently came under Mamluk control in 1291 C.E.[5]

During early Ottoman rule in Palestine, in 1564 C.E., the revenues of the village of Shefa-'Amr were designated for the new waqf of Hasseki Sultan Imaret in Jerusalem, established by Hasseki Hurrem Sultan (Roxelana), the wife of Suleiman the Magnificent.[6] A firman dated 981 H. (1573 C.E.) mention that Shefa-'Amr was among a group of villages in nahiya of Akka which had rebelled against the Ottoman administration. By 1577 C.E. the village had accumulated an arsenal of 200 muskets.[7] In the 1596 daftar, Shefa-'Amr was part of the nahiya (subdistrict) of Akka with a population of 91 households ("khana"). The taxable produce comprised "occasional revenues" and "goats and beehives". Its inhabitants also paid for the use or ownership of an oil press.[8]

It was not until the eighteenth century that the village rose to real prominence. At the beginning of the century the village was under control of Shaykh Ali Zaydani, uncle of DahEr el-Omar and leading shaykh of lower Galilee. It is also known that there was a castle in the village at least as early as 1740. After Daher al-Omar's rise to power in the 1740s, Ali Zaydani was replaced with his nephew, Uthman; a brother of Daher el-Omar. After el-Omar's death in 1775, Jezzar Pasha allowed Uthman to continue as a ruler of Shefa-'Amr in return for a promise of loyalty and advance payment of taxes. Jezzar Pasha allowed the fortress to remain intact despite orders from Constantinople that it should be destroyed.[9] Several years later Uthman was removed and replaced with Ibrahim Abu Qalush, an appointee of Jezzar Pasha.[10]

During this period Shefa-'Amr was a regional centre of some importance due to its location in the heart of the cotton growing area and its natural and man-made defenses. The significance of cotton to the growth of Shefa-'Amr is fundamental. Tax returns for the village attest to the large returns expected of this crop.[11]

Geography

Shefa-'Amr is an ancient city located in the North District in Israel at the entrance to Galilee. It is located 13 kilometres (8.1 mi) from the Mediterranean Sea and 20 kilometres (12 mi) from each of three cities, Haifa, Acre and Nazareth, where many of the inhabitants are employed. The city is located on seven hills, which gives it the name "Little Rome". The elevation of the city and its strategic location as the connection between the valleys and mountains of Galilee made it more than once the center of its district, especially in the period of Otman the son of Dhaher al-Omar, who built a castle in it, and towers around it. If you stand in a high spot in the city you can see a great view: the bay of Haifa with the sea stretching between Haifa and Acre in the west, and in other directions the high mountains of Galilee and the valleys surrounding the city.

Politics and local government

Ibraheem Nimr Hussein, a former mayor of Shefa-'Amr, was chairman of the Committee of Arab Mayors in Israel (later the Arab Follow-Up Committee) from its inception in 1975.

According to Ynetnews, in January 2008, Mayor Ursan Yassin met with officials of the Israeli state committee on the celebrations for the 60th anniversary of independence, and announced that Shefa-'Amr intended to take part in the celebrations. He stated: "This is our country and we completely disapprove of the statements made by the Higher Monitoring Committee. I want to hold a central ceremony in Shefa-'Amr, raise all the flags and have a huge feast. The 40,000 residents of Shefa-'Amr feel that they are a part of the State of Israel...The desire to participate in the festivities is shared by most of the residents. We will not raise our children to hate the country. This is our country and we want to live in coexistence with its Jewish residents."[12]

In 2011, 7,000 Christian, Druze and Muslims held a solidarity march in support of Christians in Iraq and Egypt who are suffering from religious persecution.[13]

Demographics

In 1596, Shafa'amr appeared in Ottoman tax registers as being in the Nahiya of Akka of the Liwa of Safad. It had a population of 83 Christian households and 8 bachelors.[14] No Jews were noted, but there had been a very small number mentioned in the early decades of that century.[15] The next definite indication of a Jewish presence was in the 18th century.[15]

Finn reported wrote in 1877 that "The majority of the inhabitants are Druses. There are a few Moslems and a few Christians; but [in 1850] there were thirty Jewish families living as agriculturists, cultivating grain and olives on their own landed property, most of it family inheritance; some of these people were of Algerine descent. They had their own synagogue and legally qualified butcher, and their numbers had formerly been more considerable." But "they afterwards dwindled to two families, the rest removing to [Haifa] as that port rose in prosperity."[16] Conder and Kitchener, who visited in 1875, was told that the community consisted of "2,500 souls—1,200 being Moslems, the rest Druses, Greeks, and Latins."[17]

At the time of the 1922 census of Palestine, Shafa Amr had a population of 1263 Christians, 623 Muslims, and 402 Druses.[18] By the 1931 census, it had 629 occupied houses and a population of 1321 Christians, 1006 Muslims, 496 Druses, and 1 Jew. A further 1197 Muslims in 234 occupied houses was recorded for "Shafa 'Amr Suburbs".[19] Statistics compiled by the Mandatory government in 1945 showed an urban population of 1560 Christians, 1380 Muslims, 10 Jews and 690 "others" (presumably Druses) and a rural population of 3560 Muslims.[20][21]

In 1951, the population was 4450, of whom about 10% were refugees from other villages.[22] During the early 1950s, about 25,000 dunams of the land of Shefa Amr was expropriated by the following method: the land was declared a closed military area, then after enough time had passed for it to have become legally "uncultivated", the Minister of Agriculture used his powers to "ensure that it was cultivated" by giving it to neighboring Jewish communities. Some of the land was owned by Jews.[23] Another 7,579 dunams was expropriated in 1953-4.[24] The total land holdings of the village fell from 58,725 dunams in 1945 to 10,371 dunams in 1962.[24]

Shfar'am's diverse population drawn from several different communities gives the city a relatively cosmopolitan and multi-cultural ambiance.

According to CBS, in 2009 the religious and ethnic makeup of the city was mostly Israeli Arabs (consisting of 59.5% Muslim, 26.3% Christian, and 14.3% Druze). According to CBS, in 2009 there were 35,300 registered citizens in the city. The population of the city was spread out with 44.3% 19 years of age or younger, 15% between 20 and 29, 21.9% between 30 and 44, 13.3% from 45 to 64, and 4.5% 65 years of age or older.

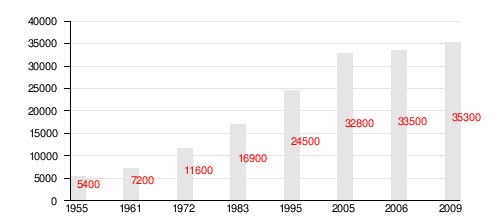

Population in Shefa-'Amr over the years:

Economy

According to the CBS, as of the year 2000, there were 7,114 salaried and 872 self-employed workers in the city . The mean monthly wage in 2000 for a salaried worker in the city was ILS 3,836. Salaried males had a mean monthly wage of ILS 4,543 versus ILS 2,386 for females. The mean income for the self-employed was 5,777. 507 people received unemployment benefits and 5,315 received an income guarantee.

Education and culture

In 2007, there were 23 schools catering to a student population of 9,140: 11 elementary schools with 5,233 students and 12 high schools with 3,907 students. In 2001, 57.7% of twelfth grade students were entitled to a matriculation certificate. In the eastern part of the city, Mifal HaPayis has built a public computer center, a public library, a large events hall and more.

Beit almusica conservatory was founded in 1999 by musician Aamer Nakhleh in the center of Shefa-'Amr. It offers a year-round programs of music studies in various instruments, and holds music performances and concerts.[25] Every year Shefa-'Amr holds a music festival known as the "Fort Festival." Arab children from all over the country compete in singing classic Arabic songs and one is chosen as "Best voice of the year." The Ba'ath choir, established by Raheeb Haddad, performs all over the country and participates in many international events. Singer Reem Talhami gives concerts all over the Arab world and Tayseer Elias is a leading musician and violin player. Butrus Lusia, a painter, specializes in icons for Christian churches.

The first plays in Shefa-'Amr were performed in the 1950s by the Christian scouts. Since the 1970s, many theaters have opened. among them the sons of Shefa-A'mr theater, Athar theater, house of the youth theater, Alghurbal Al Shefa-'Amry theater and Al Ufok theater. The largest theater in the city is the Ghurbal Establishment which is a national Arab theater. Sa'eed Salame, an actor, comedian and pantomimist, established an 3-day international pantomime festival that is held annually.

Shefa-'Amr is known for its mastic-flavored ice cream, bozet Shefa-'Amr. The Nakhleh Coffee Company is the leading coffee producer in Israel's Arab community. New restaurant-cafes have been opened in parts of the old city; those places are becoming the main cafes the youth of Shefa-Amr choose to spend their free time and special occasions in. Awt Cafe started holding musical nights where local singers and instruments players like Oud and others play for the crowd of visitors. Being a new trend in the city these nights are becoming a great success and the cafe in those nights is always full of people who come to enjoy a cultural night with their friends and families.

Arab-Israeli conflict

On August 4, 2005, an AWOL Israeli Defense Force soldier, Eden Natan-Zada, opened fire while aboard a bus in the city, killing four Israeli Arab citizens and wounding twenty-two others. After the shooting, Natan-Zada was overcome by nearby crowds, lynched and beaten with rocks. According to witnesses, the bus driver was surprised to see a kippah-wearing Jewish soldier making his way to Shefa-'Amr via public bus, so inquired of Natan-Zada whether he was certain he wanted to take his current route. The four fatalities were Hazar and Dina Turki, two sisters in their early twenties, and two men, Michel Bahouth (the bus driver) and Nader Hayek. In the days following the attack, 40,000 people attended mass funeral services for the victims. The sisters were buried in an Islamic cemetery and the men were buried in the Christian Catholic cemetery. The wounded were taken to Rambam Hospital in Haifa.

Landmarks and religious sites

- A fort was built in 1760 by the Ottoman the son of the Ottoman ruler Daher al-Omar, at the time the governor of the area, for the purpose of securing the entrance to Galilee. The fort was built on remains of a Crusader fort called "Le Seffram". The first floor of the fort was for the horses, the second floor was where Dhaher lived. Daher's fort is considered the biggest remain of the Zidans in Galilee. After the establishment of the state, the fort was used as a police station. After a new station was built in the "Fawwar" neighbourhood, it was renovated and converted to a youth center club, which has since closed down.

- "The Tower" or "al Burj" is an old Crusader fort located in the southern part of the city.

- The old market of Shefa-'Amr was once the bustling heart of the city. Now all that remains is one coffee shop where elderly men gather every day to play backgammon and drink Arab coffee. According to the mayor of Shefa-Amr, Nahed Khazem, the government has provided a budget for improving and reviving the old market and turning the area around the fort into a tourist attraction.

The Shfaram Ancient Synagogue is an old synagogue on the site of an even older structure. It is recorded as being active in 1845. A Christian resident of the town holds the keys.[26] The synagogue was renovated in 2006. The tomb of Rabbi Judah ben Baba, a well-known rabbi from the 2nd century who was captured and executed by the Romans, is still standing and many Jewish believers come to visit it.

Byzantine period tombs are located in the middle of the city. They were the graves of the 5th and 6th century Christian community. The tomb entrances are decorated with sculptures of lions and Greek inscriptions which make mention of Jesus.

In the center of the city, where the Sisters of Nazareth convent stands today, was a 4th century church called St. Jacob's Church. This church is mentioned in the notes of Christian church historians, although the church is not still standing today (the church of the monastery is where it was). Some marble columns remain, like those used to build the earliest churches.

St. Peter & St. Paul Churchis located in one of the town's peaks near the fort, it has a high bell tower and a large purple dome. The church was built by Otman, who made a promise to build it if his fort was finished successfully, so its history goes back to that of the fort. The walls of the church started to get weak so in 1904 the whole church was strengthened and improved. It remains standing today and is the main church of the Greek Catholic community of Shefa-'Amr.

Mosque of Ali Ibn Abi Talib (Old Mosque) built near the castle in the days of Suleiman Pasha.

Archaeology

Settlement in Shefar‘am has existed without interruption since the Roman period, when it was one of the cities of the Sanhedrin. Decorated burial caves were documented by the Survey of Western Palestine in the late nineteenth century, and an architectural survey was carried out in the fortress. In August–September 2008, a salvage dig was conducted in the southern quarter of the old city exposing remains from five phases in the Late Byzantine and early Umayyad periods. Finds include a tabun, a pavement of small fieldstones, a mosaic pavement that was probably part of a winepress treading floor, a small square winepress, handmade kraters, an imported Cypriot bowl and an open cooking pot. Also discovered were glass and pottery vessels.[27]

Notable residents

- Mansour F. Armaly

- Zahi Armeli (born 1957), former footballer

- Mohammad Barakeh

- Emile Habibi (1922–96), Christian Israeli-Palestinian writer and communist politician

See also

References

- ^ "Table 3 - Population of Localities Numbering Above 2,000 Residents and Other Rural Population". Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. http://www1.cbs.gov.il/population/new_2010/table3.pdf.

- ^ Conder, Claude Reignier and H.H. Kitchener: The Survey of Western Palestine. London:Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. (1881) I:343, Guerin, I, 414, TIR, 230. All cited in Petersen, 2001, p.276

- ^ Denys Pringle (1997). Secular buildings in the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem : an archaeological gazetteer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 125. ISBN 0521460107.

- ^ Abu Shama RHC (or.), IV, 487. Yaqut, p304, Both cited in Petersen, 2001, p. 277

- ^ Ibn al-Furat, Cited in Petersen, 2001, p. 277

- ^ Singer, A., 2002, p.126

- ^ Heyd, 1960, p84-85,n.2. Cited in Petersen, 2001, p.277.

- ^ Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter and Kamal Abdulfattah (1977), Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. p. 192. Quoted in Petersen, 2001, p.277

- ^ Cohen, 1973, p.106. Cited in Petersen, 2001, p.277

- ^ Cohen, 1973, p.25. Cited in Petersen, 2001, p.277

- ^ Cohen, 1973, p.128. Cited in Petersen, 2001, p.277

- ^ http://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-3501480,00.html

- ^ Shfaram: 7,000 march in solidarity with Christians

- ^ Wolf-Dieter Hütteroth and Kamal Abdulfattah (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. p. 192.

- ^ a b Alex Carmel, Peter Schäfer and Yossi Ben-Artzi (1990). The Jewish Settlement in Palestine, 634–1881. Beihefte zum Tübinger Atlas des Vorderen Orients : Reihe B, Geisteswissenschaften; Nr. 88. Wiesbaden: Reichert. pp. 94,144.

- ^ James Finn (1877). Byeways in Palestine. London: James Nisbet & Co. p. 243.

- ^ C. R. Conder and H. H. Kitchener (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine. I. London: The Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. p. 272.

- ^ J. B. Barron, ed (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine. Table XI.

- ^ E. Mills, ed (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine. p. 96.

- ^ Government of Palestine, Village Statistics, 1945.

- ^ Sami Hadawi (1957). Land Ownership in Palestine. New York: Palestine Arab Refugee Office. p. 44. http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015010745381.

- ^ Kamen (1987). "After the Catastrophe I: The Arabs in Israel, 1948-51". Middle Eastern Studies 23 (4): 453–495. doi:10.1080/00263208708700721.

- ^ Sabri Jiryis (1973). "The Legal Structure for the Expropriation and Absorption of Arab Lands in Israel". Journal of Palestine Studies 2 (4): 82–104. doi:10.1525/jps.1973.2.4.00p0099c.

- ^ a b Sabri Jiryis (1976). "The Land Question in Israel". MERIP Reports 47: 5––20+24–26.

- ^ Beit al-Musica Conservatory

- ^ How the other fifth lives

- ^ Shefar‘am Final Report

Bibliography

- Abu Shama (d.1267) (1969): Livre des deux jardins ("The Book of Two Gardens"). Recueil des Historiens des Croisades, Cited in Petersen (2001).

- Cohen, A. (1973), Palestine in the Eighteenth Century: Patterns of Government and Administration, Hebrew University, Jerusalem. Cited in Petersen, (2001)

- Conder, Claude Reignier and H.H. Kitchener (1881): The Survey of Western Palestine: memoirs of the topography, orography, hydrography, and archaeology. London:Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. vol 1 p. 271-3, 339 -343, map V

- Jeeran.com homepage

- Guérin, M. V. (1880): Description Géographique, Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine. Galilee 1 part. p 410-411

- Heyd, Uriel (1960): Ottoman Documents on Palestine, 1552-1615, Oxford University Press, Oxford. Cited in Petersen (2001)

- Herzog, Chaim and Shlomo Gazit, The Arab-Israeli Wars, Vintage books, 2005.

- Ze'ev Vilnai, "Shefa-'Amr, Between the past and the present",Jerusalem 1962.

- Palmer, E. H. (1881): The survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English name lists collected during the survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and explained by E.H. Palmer. p.116,

- Petersen, Andrew (2001): A Gazetteer of Buildings in Muslim Palestine: Volume I (British Academy Monographs in Archaeology) Shafa Amr p. 276-280

- Rogers, Mary Eliza, (1865): Domestic Life in Palestine (Also cited in Petersen, 2001)

- Singer, A. (2002). Constructing Ottoman Beneficence: An Imperial Soup Kitchen in Jerusalem. Albany: State of New York Press.

External links

- Shefa-'Amr official website (Arabic)

- Information about Shefa-Amr (Arabic)

|

|||||||||||||